Jeff Dirks is fascinated by new technologies like generative AI. But when it comes to implementation, the chief information and technology officer of workforce augmentation firm TrueBlue chooses a path that trails early adopters. “We’re in the early majority,” is the CIO/CTO’s blunt self-assessment.

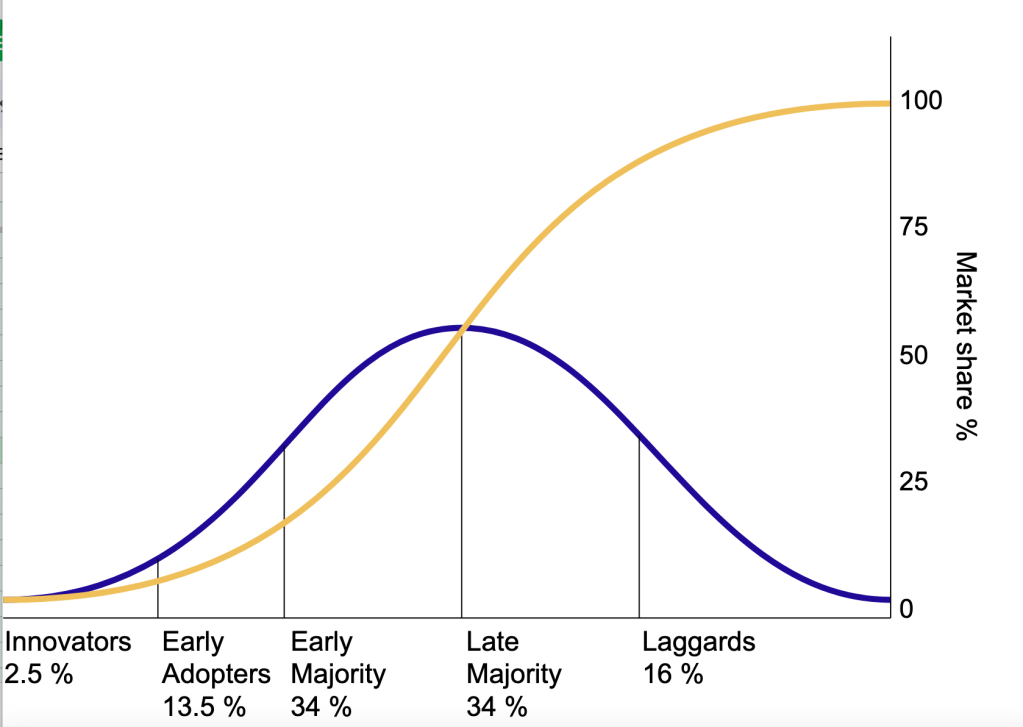

Although many IT leaders would like to think of themselves — and have others think of them — as in the vanguard of new technology adoption, the vast majority find themselves in the middle of a bell curve, with innovators leading the way and laggards trailing behind, according to Everett Rogers’ diffusion of innovations theory [see chart]. But there is no one “right” place to be along the curve. The trick is to know where your organization belongs — and to make the most of it.

The diffusion of innovations theory, published by Everett Rogers in 1962, places most organizations in the middle of a bell curve of technology adoption.

Public Domain

“Organizations that are willing to explore new technologies and be the first in their industry face the highest risk and highest potential return on new technology. But that is very few companies,” says Brian Burke, research vice president for technology innovation at Gartner. A far savvier approach for most organizations is to exploit adjacency — to keep an eye on innovators in similar industries and, when the time is right, adopt the technologies they are using.

“If you’re in banking and you see that an insurance company has adopted a technology, you might adopt it as the first in your industry, gaining a first-mover advantage with less risk,” says Burke.

Dirks buys into that philosophy for TrueBlue, whose core business, PeopleReady, is to provide a platform for efficiently matching day laborers with companies that have contingent labor needs. For TrueBlue, the so-called “gig-economy” companies like Uber and Lyft and venture-backed competitors such as Wonolo and Instawork are adjacent bellwethers. While such companies are technology-first, TrueBlue is evolving from brick-and-mortar to digital, a path that calls for incremental, rather than radical innovation.

TrueBlue’s award-winning Affinix app, which aims to make recruiters more efficient by predicting which candidates have the highest probability of success, implements data science, machine learning, and RPA, technologies that Dirks calls mainstream. Consistent with that approach, Dirks is exploring the use of blockchain technology to create a trusted ledger of contingent laborers’ credentials, including facets such as drug and background checks. Although blockchain is no longer new, using it in this way would be a first in the day-labor industry, Dirks says.

Institutionalizing innovation

Far from the fast-track of venture-backed data science, government agencies often are found among late-majority and laggard organizations. “In the public sector, there is a propensity to not rock the boat. But that’s not always the right approach,” says Feroz Merchhiya, CIO and CISO of the City of Glendale, Ariz. He ranks the city between early majority and late majority, depending on the project.

When the state of Arizona centralized the collection of state sales taxes several years ago, municipalities such as Glendale struggled with the inefficiency of collecting taxes, sending them to the state, and then receiving their share back in disbursements.

“We did not have a solution to do this. It was very cumbersome for cities as well as businesses. There were a slew of complex interactions that needed to take place,” says Merchhiya. Having scouted industry events and discussed the situation with analysts, he and his team discovered there was no off-the-shelf solution.

“When we realized there was nothing available, we thought it would be a good idea to develop it on our own,” he says. With his own staff of 50 and a like number of contingent workers, Merchhiya led the development of AZ Tax Central, which Glendale is now using and making available to other cities for a charge that covers costs only.

With that successful project under his belt, Merchhiya is seeking to institutionalize the innovation process. Knowing that innovation in government can never succeed without administrative support and budget dollars, Merchhiya convenes annual meetings with civic officials to learn the issues they are facing and to brainstorm how technology might address them.

“It’s one thing to do accidental innovation. It’s another to put a process in place. I’m trying not to be an accidental innovator — the only way I can do that is to engage the business by inviting everybody to get together and have a conversation,” he says.

Tailoring innovation for real-world impact

Engagement is also important at the District of Columbia Water and Sewer Authority (DC Water), an agency that serves the nation’s capital and the surrounding region, including Dulles Airport. “You have to embrace people to make them comfortable with suggesting ideas — and not being disappointed if their idea doesn’t move forward,” says Thomas Kuczynski, vice president of IT at DC Water, which is responsible for 1,300 miles of water distribution pipe, and 1,900 miles of sewer pipe.

Although DC Water’s budget does contain an allocation for experimental work, IT must keep its eyes on real-world challenges. Kuczynski says the agency’s technology adoption sometimes falls into each of Rogers’ classifications, depending on the project. “Our focus is to have a positive impact on the business as quickly as possible,” says Kuczynski. “We focus on opportunities where we believe we can create efficiencies and improve operations.”

For example, DC Water began using an AI-based product called PipeSleuth to inspect the sewer system. An improvement over previous CCTV systems, PipeSleuth sends a sausage-shaped drone on wheels through the system to look for pipe anomalies. Using deep-learning, neural-network technology, it tags defects and produces a report, rather than requiring operators to view reams of video as is necessary with CCTV-based systems.

Using PipeSleuth has enabled DC Water to substantially reduce the cost of pipe inspections, allowing the agency to inspect more pipe at the same cost. “The more we can inspect regularly, the more improvements we can make because we better understand the system. If we can do more inspections per dollar, we can apply that repair dollar to a bigger problem because we know more about my system,” says Kuczynski.

Another DC Water innovation is an event management system that integrates in a single dashboard SCADA data, inbound calls, work orders, USGS data, rain-level gauge, and other IoT inputs from sensors tracking water pressure, flow, and level. The system also tracks personnel and vehicles via GPS to dispatch repair staff to the highest priority trouble spots quickly.

“The dispatch system integrates IT and OT in a single dashboard. Now we can manage emergencies more effectively. In the past, if we got 20 calls about one problem, there might be 20 work orders. Now those calls are consolidated into one work order,” he says.

The art of selection

Ty Tastepe, senior vice president and CIO of Cedar Fair Entertainment Company, an operator of 13 amusement parks and resorts in the US and Canada, says his company tends to be in the “fast-follower” category, a space that’s generally recognized to sit somewhere between early-adopter and early-majority groupings.

“We look at technology implementations not only in our own industry but also in adjacent industries like retail and food services,” Tastepe says. He adds, “If there were no proven technology, we would entertain being an early adopter or try to pilot something new to address a business challenge.”

“The good ideas are plentiful — the challenge is to identify the must dos, and whether a project fits within budget and resource constraints,” says the CIO. Because Cedar Fair is a public company, Tastepe thinks in terms of delivering results. He says new technologies must answer yes to at least one of three questions: Does it generate revenue? Does it improve efficiency? Does it satisfy compliance requirements?

“There will always be budgeting constraints; that’s why due diligence up front is important. We do a discovery process. Once the business sponsor puts together a charter for an initiative that can be enabled by a technology implementation, we discuss the merits of the initiative at the portfolio management committee,” he says. The next step is to flesh out the business model and the costs, sometimes with the assistance of a partner. “If we decide to move forward with the project, we might do a proof of concept before we deploy at scale,” he adds.

Gartner’s Burke agrees with Tastepe that winnowing down the field of technologies to a few plausible candidates is essential. “When you’re scouting new technologies it’s a bit of an art as well as a science,” says the analyst. Typically, organizations scan several hundred technologies, a number that must be reduced to a couple dozen for serious study, Burke says.

Knowing when to pull the plug

One company that is widely recognized to be in the innovator category is Amazon.com,

which willingly invests in technology-heavy concepts such as Amazon Go, a convenience story with no checkout. Although Amazon has built a couple dozen such stores, the giant retailer recently announced the closure of several. In addition to reining in Go stores, Amazon.com has reportedly curtailed its drone delivery initiative. While such explorations and reversals are more than most companies can risk, they underscore the importance of continually evaluating pilots to ensure there is enough warranted value in going forward with the concept.

“In Amazon’s case, they are very good at testing technology and then abandoning it if it doesn’t work,” says Ananda Chakravarty, vice president of research for retail merchandising and marketing at IDC. One reason for the Go retrenchment, according to the analyst, is that the cost of cameras dropped significantly, making them a better technology choice than the sensors that Go implemented to track inventory on shelves.

Even so, according to Chakravarty, behemoths like Amazon and Walmart, which has also experimented with Scan-and-Go checkouts and delivery drones, can afford the luxury of trying — and learning from — things that others cannot.

“There’s some real value-added to a test-and-learn approach,” says the analyst. For example, he explains, Amazon.com initially planned to sell Go technology to other retailers, and when that didn’t pan out, the company decided to target Go to niche markets such as airports, stadiums, and transportation venues, where consumers place the highest value on the convenience of a frictionless experience.

Checks and balances

Rajiv Garg, associate professor of information systems and operations management at Emory University, says putting together a diverse team to evaluate new technologies is an essential step. The group should encompass multiple corporate departments and a variety of demographics. “You might need a millennial on your team to ask how your organization is impacting the environment and society,” he suggests. Once the team is complete, he advises, turn them loose to explore.

“Send them to conferences, buy them VR headsets. If the team doesn’t like one technology, that’s fine because they might find something else they like,” says the professor. Generative AI has reached a point at which it demands to be evaluated, according to Garg. “ChatGPT and DALL-E are going to be embedded in our work somehow. You need to engage employees and use them in your workplace,” he says.

Too often, says Gartner’s Burke, the excitement of working with new technologies causes organizations to jump the gun, failing to perform due diligence ahead of time.

“Companies that have assessed a tech opportunity before they launch a proof of concept are a small minority of companies. In contrast, most organizations identify a nifty technology and then rush into a pilot without having done the easier thing — to determine whether it will actually help them in some way,” says Burke.

Even if most organizations could benefit from more careful up-front analysis, gaining an edge in the market ultimately depends on the willingness to give new technologies a try.

“We like taking a lot of swings. The more swings you take, the higher the probability that one of them will hit something translating into competitive advantage,” says Dirks.

Innovation

Source: cio.com